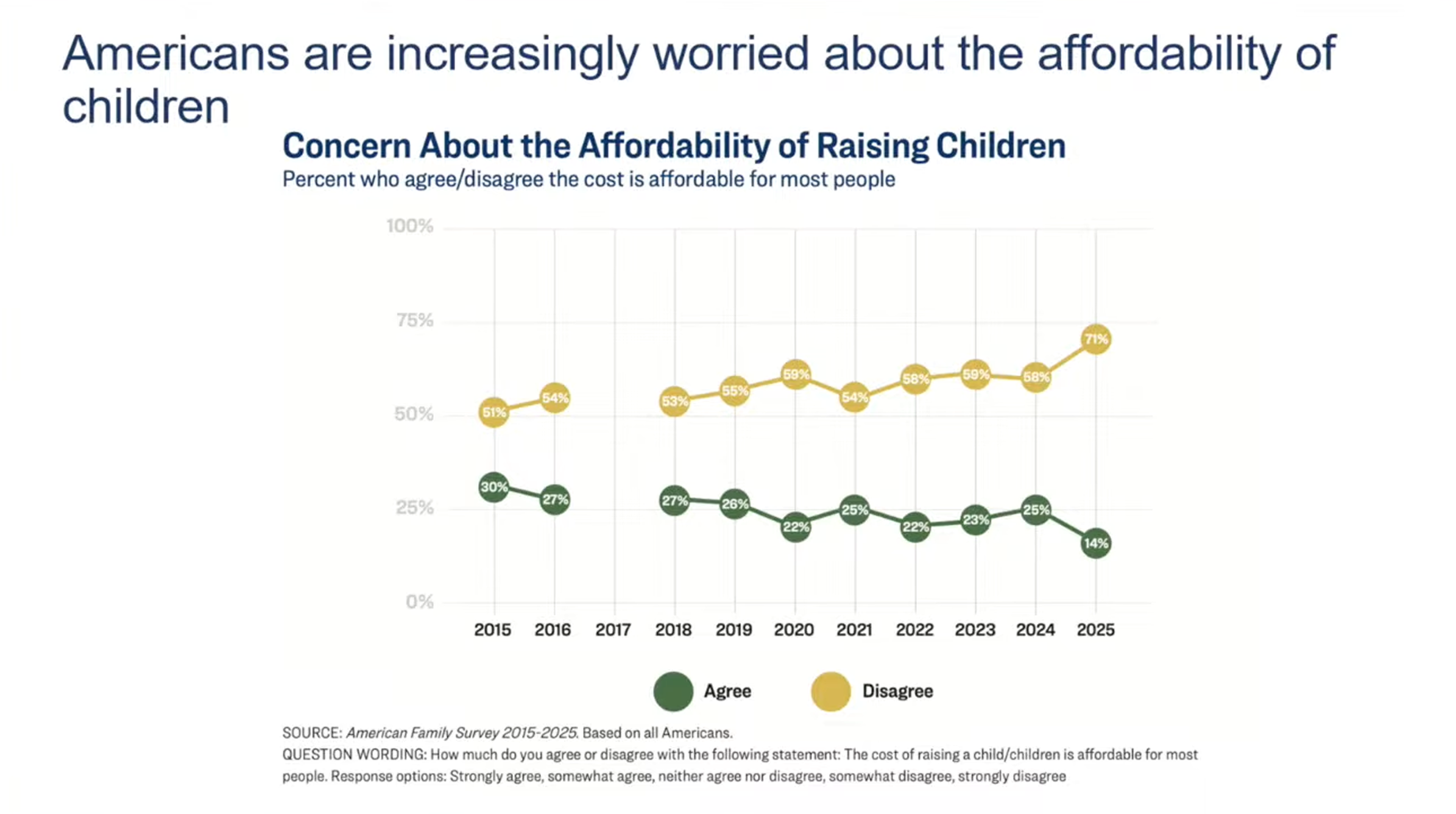

Parenting today feels like a ball of contradictions: be present but not hovering, responsive but autonomy-supportive, lean into their interests but get out of their way. While technology helps us work and stay connected, it’s turned homes into battlegrounds over screens, social media, and gaming. Anchors that parents once clung to – reliable schools, college as a predictable pathway, jobs for those who worked hard – have loosened, or become unmoored. Even the simple reality of having kids feels out of reach for many: 71% of Americans disagree that raising children in America is affordable. In 2015 that figure was 51%.

The result is exhaustion, confusion and a deep loss of agency. Parents worry that technology is harming their children and that schools aren’t preparing them. They worry about mental health, negative peer groups, and “staying on track,” even though few know what the right track is (Champion et al., 2023). A record low of 35% of Americans are satisfied with the quality of K12 education, an eight percentage point drop from last year. Admittedly, parents with kids already in the system seem to have a confirmation bias and are happier with what they are getting (74% completely or somewhat satisfied) even though only 41% of them actually think that their kids are being well prepared for college. A paltry 30% think they are being prepared for work.

Another disconnect was reflected in research Rebecca Winthrop and I conducted for our book via a Brookings-Trancend survey, where 26% of tenth graders said they loved school while 65% of parents thought their kids loved school. A third of tenth graders say they get to develop their own ideas in school; about 70% of parents think they do.

We Want Thinkers Who Can Do Things

Americans disagree on many things about education, but parents across demographics want kids who can think critically, solve problems, and make decisions. Critical thinking has remained a top priority in Populace’s Purpose of Education index since 2019. This is likely to continue to increase for two reasons: AI can increasingly think for us (coming after social media already fractured attention spans). We need to know how to think so the machines don’t do it for us, and so we know how to work with AI. Secondly, achievement is declining as problems are rising.

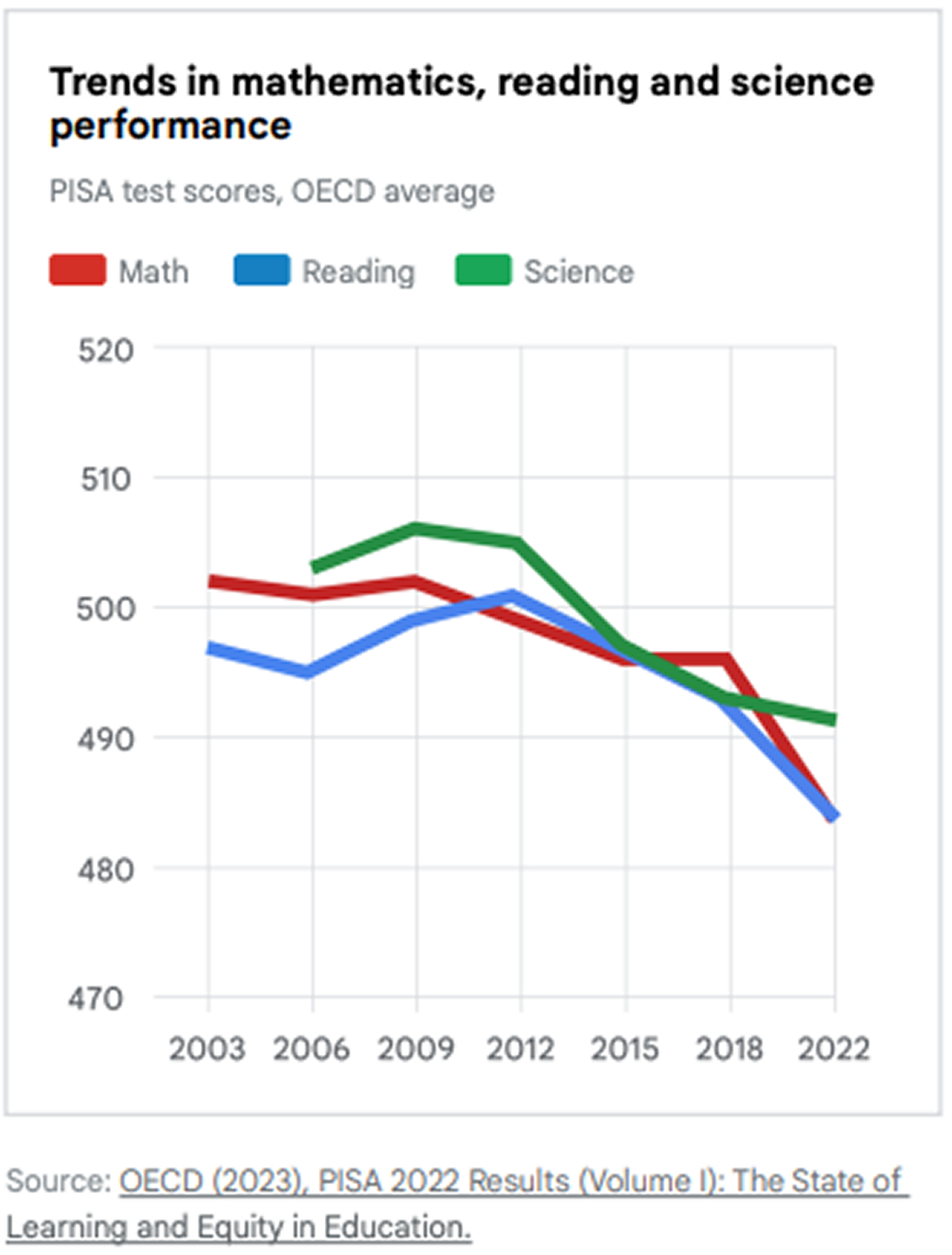

Despite billions invested in education, performance on PISA and NAEP, among other tests, is falling.

Even if standardized tests are a narrow measure of achievement, worsening proficiency in math, reading, and science, the very subjects schools prioritize, should alarm us. When kids report achievement pressure as a top stressor, yet perform worse on academic measures, it’s a clear signal: the system is not delivering academic returns. Nor is it building the capacity required to handle the complexity of the world they’re inheriting. Teachers report that foundational learning skills – self-control, cognitive flexibility, the ability to sit with frustration – are worsening. Our response has been to double down on what is easy to measure instead of what works: meaningful, relevant, rigorous work that builds knowledge and offers opportunities to stretch kids’ thinking.

Parents want kids who can do things, not just pass tests. Before COVID, respondents to a Populace survey ranked “prepare for college” as their 10th highest priority for K–12 education; by 2023, it had dropped to 47th. For four years running, Americans’ number one priority has been “develop practical skills” – managing money, preparing a meal, making an appointment. We might expect these to be taught at home. The fact that we now ask schools to teach them reflects parents’ overwhelm and need for support. Across groups, the common thread is hunger for schools that build both thinking and doing – capable citizens who can navigate complexity and daily life.

Technology, Pressure, and Fragile Adults

Parents hold a mix of fear and hope about technology. Recent surveys show many parents think AI could undermine children’s basic skills even as they hope it can support learning. They are whiplashed by tech’s broken promises; social media that was supposed to connect us often hooks, isolates, and targets young people where they’re most vulnerable. Stories of students who coast through assignments with AI and never build their own thinking muscles feel like warnings. Parents sense a mismatch: if kids are less able and jobs more demanding, their children are not in good shape.

At the same time, many families are financially stressed: one third reported having an economic emergency (not enough food, foregoing medical attention) in the past year. Childcare, housing, healthcare, and college costs have soared while wages have not kept pace. Under conditions of constant fear and scarcity, learning and thriving become much harder. Parents and caregivers are struggling too. Data from Making Caring Common show that depressed teens are far more likely than non-depressed teens to have a depressed parent, and anxious teens are far more likely to have an anxious parent. Relationships and communities are fraying just as kids need them most; adults and young people spend less time with friends and in community, and isolation is rising.

Parents need schools that build academic resilience, embrace intellectual rigor, build for civic thriving, center engagement, and provide diverse pathways for success.

They also need a lot more support.

From Achiever Mode to Explorer Mode

In promoting our book and talking in schools and to parents, Rebecca and I have heard deep, widespread frustration with a system that rewards Achiever mode. This is the learning state where kids frantically work to collect gold stars for everything put in front of them, even if they don’t understand what they are trying to win. Parents also dislike the pervasive apathy produced by Passenger mode: kids coasting along, showing up but not really learning (more than 50% of kids surveyed, we found).

They want a system that rewards what we call Explorer mode: the ability for kids to figure out who they are and what they care about, and to develop the learning muscles to go after it. This includes finding their spark, becoming good thinkers, and developing into capable, confident doers. What they have instead is a system that demands and rewards conformity around a narrow and increasingly competitive set of academic and pre-approved extracurriculars. Students are corralled towards a limited set of outcomes deemed “success” rather than being encouraged to explore ways they can find their own path to success and fulfillment. The result is endemic disengagement (Anderson, Winthrop 2025). It is not surprising that they struggle to imagine a system that nurtures a broader set of winners, or offers a more expansive definition of success.

Systems change slowly, so many parents turn inward, trying to upgrade themselves rather than school. This is a thankless task amidst deep dislocation and uncertainty. Parents want assurance that their significant investment in their kids – financial, yes, but more so the investments of energy and deep love – will pay off, that their kids have a shot at a meaningful life. Right now it is unclear where that assurance will come from.