Three eight-year-olds in Mr.Cook’s classroom designed an AI tutor, then “… stress-tested it with a quality assurance process more rigorous than most commercial edtech platforms. They typed inappropriate requests, tested whether it would do their homework, tried to make it play games. Each failure became a design decision. These children learned: they control these tools. The AI doesn’t make decisions. They do.” (Connected Classroom, October, 2025. https://connectedclassroom.org/perspectives/students-control-ai-not-use-it).

This is remarkable because our education systems have been suppressing these capacities for 60 years. In the 1960s, George Land tested creative problem-solving on behalf of NASA. He found that 98% of five-year-olds scored at genius level. By age ten, only 30%. As adults? Only 2%. Land’s conclusion: the more time young people spend in school settings, the less able they become to engage in creative problem-solving (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZfKMq-rYtnc). But when given the opportunity, as Cook’s students demonstrate, something different emerges.

When young people learn how to use AI tools, they become designers, authors, creators, and problem-solvers…not just consumers. They develop informed agency: the practical, embodied knowledge about how things work, coupled with a belief in their efficacy that enables them to act. And, as Cook’s students demonstrate, this strengthens the capacity to meaningfully partner with technological systems.

As AI capabilities accelerate, what competencies do all of us need to develop that will make it possible to exercise informed agency in learning, work, relationships, and civic participation?

The Inflection Point

The World Economic Forum predicts 170 million new jobs by 2030, with 92 million displaced and 39% of existing skills outdated (https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/).

But I would argue the greater risk isn’t job displacement. It’s raising Gen Z and Gen Alpha to undertake tasks that machines now handle more effectively, while never providing them with the opportunity to develop the distinctly human capacities essential for building relationships, sustaining democracies, and creating purposeful lives.

Consider Maya, a high school junior who excels at mediating peer conflicts and organizing community projects—capacities nowhere reflected in her transcript. Or James, a 35-year-old laid off from manufacturing, with no language for the problem-solving and adaptive thinking that would make him valuable in emerging roles.

The cost: disengaged learners, adults unprepared for change, fragile communities, and millions unable to develop or describe the competencies AI cannot replicate – the same competencies that enable human-AI partnership for solving complex problems.

A Strengths-Based Approach to Lifelong Growth

AI can now handle the procedural knowledge that is the hallmark of the US schooling system. This creates the opportunity to recenter distinctly human competencies: designing solutions, sustaining our well-being, expressing oneself in powerful ways across many media, advocating for ourselves and others, and engaging in critical analysis and discernment (https://www.redesignu.org/future9).

Consider designing solutions – a competency that weaves together inquiry, empathy, iteration, and systems thinking. A seven-year-old identifies that playground equipment excludes wheelchair users, interviews classmates about their experiences, sketches possible designs, and tests prototypes. A 28-year-old recognizes that her company’s return-to-office policy is causing key talent to leave, gathers data across teams, proposes a flexible hybrid model, and pilots it with one department. A 70-year-old sees neighbors struggling with food access, maps community assets, and co-creates a neighborhood sharing network.

These are competencies we use across contexts throughout our lives: as five-year-olds resolving playground disputes, as humans solving problems in our workplace or community, as parents building families, as elders passing wisdom forward.

When we define Future-ready Competencies in terms of human development, and make performance levels transparent, observable and action-oriented, individuals of any age or stage gain the opportunity to nurture informed agency, as they assess their capacities, identify where growth would support flourishing, and pursue development in contexts that matter – learning settings, workplaces, family and community spaces, or personal practice.

The danger of this moment is to over-index on workforce skills, and adolescent readiness, while missing the developmental arc of competency development that begins in early childhood. Flourishing requires attending to competencies across the full span of development – as neural networks form, as identities develop, as life circumstances shift.

What Research Tells Us

How do we determine which competencies matter most? Through rigorous synthesis of cultural values and aspirations, coupled with research across cognitive science, biology, psychology, and human development.

Over the past fifteen years, I’ve met with educators, parents, community and industry leaders, academics, politicians and young people to find out what they believe “young people should get really good at.” Across different roles, political affiliations, class, culture, and geography, there are consistent throughlines: we believe that communicating, problem-solving, and navigating conflict, are essential.

From here, we need to be much more rigorous in looking to research, ensuring that our definition of what a competency is, and how it’s learned across ages and stages truly reflect what is known: creating competencies that can’t be described and observed at different development stages sets everyone up for failure.

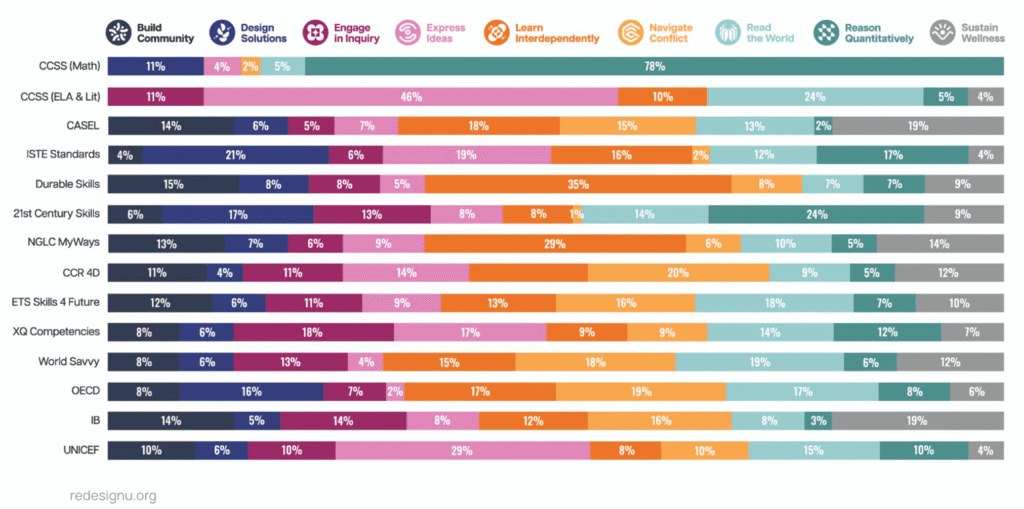

When we were working on reDesign’s Future9 Competency Framework we undertook three checks on our competencies: (1) We brought them to industry, community, politicians, educators and young people for feedback. (2) We engaged researchers to apply their expert knowledge. And (3) We cross-walked the Future9 with 14 leading US and international competency frameworks.

The analysis (see chart below) revealed remarkable convergence in the field: 13 of 14 frameworks attend to competencies across community building, design, inquiry, expression, agency, conflict navigation, critical analysis, quantitative reasoning, and well-being. Only the US State Standards stand apart – not designed as a competency framework at all, they address only two of these nine domains, revealing the absence of any systematic commitment to developing and measuring what matters most.

The Path Forward

The opportunity of this moment is to reorient our learning systems in school, work, and community toward the development of uniquely human competencies: to ensure that the “genius” of five-year-olds and the design capabilities of eight-year-olds will grow and deepen, rather than atrophy.

This isn’t aspirational thinking. It’s a pragmatic response to the world we’re already living in. Countries from Singapore to Finland to Brazil are reorganizing education around these frameworks. Districts in Kentucky and employers in Tennessee demonstrate what becomes possible with shared competency language. The tools, research, and examples exist. What we need now is coordinated commitment to make competency development as visible and systematically developed as we currently make test scores. The age of AI makes this necessary.